Yucatan History

Human activity on the Yucatan Peninsula goes back as far as 9,000 BC. when small groups of hunter-gatherers used the limestone caves as temporary shelters. Not much is known about this period, but in several caves human remains have been found along with stone artefacts. From around 3000 years ago the Mayan culture began to spread out from the first ceremonial centers in the south of Guatemala.

Buy at AllPosters.com

Eventually people went north to populate the Yucatan peninsula. Slash-and burn-agriculture mingled with shamanism and an incipient social structure paved the way for Classic Mayan Civilization between 250 A.D. and 900 A.D. Their 'golden age' were the sixth and seventh centuries, when divine kings ruled over vast ceremonial kingdoms and life was defined by ritual and cosmic warfare.

Despite their almost total lack of technology, the Maya arrived at admirable intelectual and artistic heights. They developed the only complete writing system of the Americas and captured time in a unique way. Rich royal burials have been found at Palenque and Ek Balam, among others. And even after dinasties disintegrated and most of the Classic powerhouses in the central lowlands had collapsed, Maya civilization continued to flourish for several centuries to come in northern Yucatan.

From 800 onwards buildings in west Yucatan were decorated in the upcoming Puuc style or Maya baroque. At about the same time the Itza arrived and began their rise to power. And even after the downfall of Chichen Itza in 1204 and the subsequent plundering of Mayapan in 1441 the Maya kept up their activities of commerce and trade along the Yucatan coast. Many smaller sites were still occupied when the Spanish arrived.

First Contact

Buy at AllPosters.com

Soon after the Spanish established themselves at Cuba the first ships arrived at Cabo Catoche. Official exploration of the Yucatan coast began in 1517, with two more expeditions to follow.

Hernan Cortes set sail in November 1518. He first explored the eastern coastline through Punta Allen in what is now Si'an K'aan biosphere. Imagine yourself the port of Tulum (called Zama by the Maya) full of activity. Cortes was so impressed by the white buildings and all he saw that he compared the place to Seville.

Serious attempts to colonize the peninsula however were made only after the conquest of Tenoch, the Aztec capital, in 1521. Captain Francisco de Montejo arrived in 1527. He was actually aiming to beat his rival Pedro the Alvarado for the governorship of Honduras. After playing his part in the conquest of the Aztecs he'd went back to Spain, to return to Mexico a few years later holding the title of 'Adelantado'. This bestowed upon him official authorization to conquer and colonize new land for the Spanish crown, but in return he himself had to finance his expedions.

Buy at AllPosters.com

De Montejo never actually lived in the Yucatan. He kept his hopes up for the governorship of Honduras and preferred to stay in Chiapas, from where he led his expeditions. Resistance turned out to be fierce and apart from the northwestern corner of the Yucatan the Maya were never really defeated. He was driven from the land several times and an attempt to establish a capital at Chichen Itza was smothered in 1535.

His bastard son, Francisco de Montejo 'El Mozo', invaded Yucatán with a large force in 1540 and founded San Francisco de Campeche. Two years later he established his capital on the ruins of T'ho and renamed the city Mérida. A third colonial town called Valladolid was founded by his cousin in 1543.

The northwestern Maya groups were subdued when El Mozo forged an allegiance with one of the Xiu lords called Tutul Xiu. However native rebellions against Spanish rule continued to be a problem for centuries. A large revolt led by Can Ek in 1761 ended with the torture and execution of its leader. Thus, allthough officially proclaimed as 'conquered' in 1547 the Yucatan was never totally pacified until well into the twentieth century.

The church arrives

Soon after Spanish authority was established the religious conquest began. In Yucatan the undertaking was monopolized by the Franciscan order. With the religious zeal of their time, the monks began to preach about the Christian God.

The Maya were baptised and renamed as Jose, Juan, Francisco, Maria and Ana. Their pre-columbian deities were replaced by the Saints of Christianity and any pagan beliefs and rituals were suppressed. Until 1542 when the Pope declared they had a soul, the natives of the Americas were regarded as nothing more than animals. Unfortunately the fact that they were now human did not liberate them from being exploited as slaves.

Their cultural heirloom was devastated. Sacred temples were demolished and re-used as building material for colonial mansions and churches. Only 4 fragments survived the burning of all Maya books ordered by Diego de Landa in 1562. In his fervor to wipe out idol worship and human sacrifice he organized a so-called auto-de-fe in the town of Mani. Thousands of clay idols were destroyed during this single event, and - a fact that is often mentioned as only a sidebar - several hundreds of Maya were killed.

De Landa was was recalled to Spain on charges of excessive harshness, but along with a reprimande he also obtained his nomination as the fourth Bishop of Yucatan so he returned in the 1570's. His defense against the charges was a book called la " Relacion de las Cosas de Yucatan".

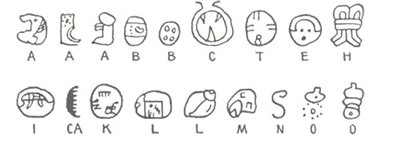

These writings are now considered to be the most detailed account of Maya social organization from the first contact period. One of his informers even passed on to him what he (De Landa) erroneously thought to be an alphabet. His mis-interpretation has later been invaluable in cracking the code of Maya hieroglyphic writing.

On the surface, the Maya embraced the Christian God and Saints. But many took it on as an addition to rather than a replacement of their old beliefs. The Yucatan Maya today continue to worship the ancient agricultural deities with prayer, incense and offerings. Many Pre-Columbian temples were still being used well into the Colonial period.

Turbulent times

In 1821 the Yucatan peninsula became part of independent Mexico. Discontent with central authority however lead to several attempts of separation in the first half of the 19th century. Treaties between the local and central government were not respected and hostilities lead to the proclamation of the Republic of Yucatan in the early 1840's.

A Mexican invasion was repressed in 1843, but at the same time a commercial blockade made governor Miguel Barbachano renegociate terms. Once more the territory was reincorporated into the Mexican Republic, only to re-declare independance a few years later.

The Caste War

The execution of three Maya rebels in Valladolid in 1847 is considered the beginning of the Caste War or Guerra de Castas. The Maya of the southeast took to arms in their refusal to acknowledge the hispanic political and economic establishment in Merida. This major revolt turned out to be quite successful. So successful, in fact, that the government offered sovereignity over the peninsula to any nation that would come to aid. They were desperate indeed!

The Cast War was most intense in 1848. At that point the Maya were controlling almost all of Yucatan with the exception of Campeche and Merida. Had they realized the extent of their strategic situation then possibly today the peninsula would be either an independent nation or belong to the British Commonwealth like Belize.

Being farmers however, when the rains came they interrupted the battle to go plant their crops, just like their ancestors who had fought their cosmid wars only in dry season. As a consequence the republican troops were able to break the siege and Yucatan was once more united with Mexico.

Meanwhile however the eastern part of the peninsula remained under Maya control. Periodically there were uprisings. The Maya were now inspired by the cult of a Talking Cross at a town called Chan Santa Cruz, later renamed Felipe Carillo Puerto. The Cross gave them devine authority to continue their resistance. Chan Santa Cruz was proclaimed the capital of an independent Maya state and recognized by Queen Victoria because of her commercial interest in British Honduras (Belize). Finally in 1901 the area was occupied by the Mexican army and gradually, peace returned.

Green Gold

Possibly the most prosperous period in Yucatan was the end of the 19th and early 20th century. These were the decades of the henequen boom. Rightfully nicknamed the 'green gold', the fibers of the henequen plant (sisal) for making rope became a lucrative export crop when upcoming modern industry and commercial freightliners needed the rope to drive their machines.

Henequen cultivation resulted in over 300 haciendas which are now in various states of decay. The remains of manor houses and factories are being remodelled as luxury restaurants and hotels. Occasionally they are used as a filmset. Imagine the wealth of the hacienda owners back then: the city of Mérida had electric streetlights and trolley cars before Mexico City did. Mérida reportedly counted more millionaires than anywhere else in the Americas at the turn of the century.